5 Big Idea Deep Work Cal Newport

Big Idea#1 Deep Work Vs. Shallow Work

Big Idea#2 Shut down complete + Zeigarnik Effect

Big Idea#3 Hard to Reach

Big Idea#4 Will Power

Big Idea#5 Fixed schedule productivity

Big Idea#6 Multi-Tasking / Task Switch

Deep Work Vs. Shallow Work

SHALLOW WORK: Non Cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

The Deep Work Hypothesis: The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive.

Two Core Abilities for Thriving in the New Economy

- The ability to quickly master hard things.

- The ability to produce at an elite level, in terms of both quality and speed.

If you haven’t mastered this foundational skill, you’ll struggle to learn hard things or produce at an elite level.

This brings us to the question of what deliberate practice actually requires. Its core components are usually identified as follows: (1) your attention is focused tightly on a specific skill you’re trying to improve or an idea you’re trying to master: (2) you receive feedback so you can correct your approach to keep your attention exactly where it’s most productive. The first component is of particular importance to our discussion, as it emphasizes that deliberate practice cannot exist alongside distraction, and that it instead requires uninterrupted concentration.

The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance,” he dedicates a section to reviewing what the research literature reveals about an individual’s capacity for cognitively demanding work. Ericsson notes that for a novice, somewhere around an hour a day of intense concentration seems to be a limit, while for experts this number can expand to as many as four hours – but rarely more.

High-Quality Work Produced = (Time Spend) X (Intensity of Focus)

Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hour rule

- Elite performer had each totaled 10,000 hour of practice

- Good students had totaled 8,000 hour of practice

- Future music teachers had totaled 4,000 hour of practice

Elite performers set goals and break down the process. They know exactly what process they are going to practice, what time, and location.

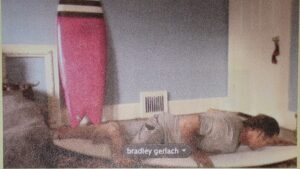

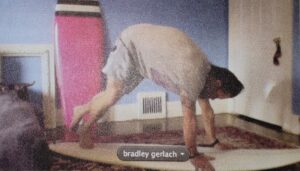

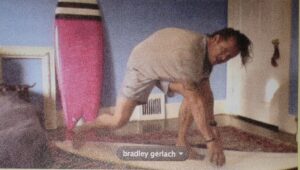

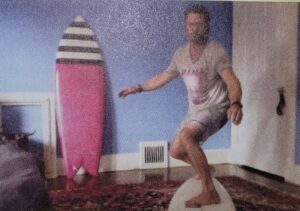

This illustration from 4 hour Chef: How Bradley Gerlach break down the process when he practices surfing.

He practices step 1 to get into perfect motion, then practice step 2. Once he practiced all 4 steps. He then combines all 4 steps together.

|

|

|

|

Shut down Complete + Zeigarnik Effect

Zeigarnik Effect: Incomplete tasks will continue to dominate our attention. It tells us that if you simply stop whatever you are doing at five p.m. and declare, “I’m done with work until tomorrow,” you’ll likely struggle to keep your mind clear of professional issues, as the many obligations left unresolved in your mind will keep battling for our attention throughout the evening.

Shut Down Complete: When you’re done, have a set phrase you say that indicates completion (To end my own ritual, I say, “Shutdown complete”). It provides a simple cue to your mind that it’s safe to release work-related thoughts for the rest of the day.

At the end of the workday, shut down our consideration of work issues until the next morning – no after dinner email check, no mental replays of conversations, and no scheming about how you’ll handle an upcoming challenge; shutdown work thinking completely. If you need more time, then extend your workday, but once you shut down, your mind must be left free.

As any busy knowledge worker can attest, there are always tasks left incomplete. The idea that you can ever reach a point where all your obligations are handled is a fantasy. Fortunately, we don’t need to complete a task to get it off our minds.

The psychologist Roy Baumeister, who wrote a paper with E.J. Masicampo playfully titled “ Consider It Done!” In this study , the two researchers began by replicating the Zeigarnik effect in their subjects (in this case, the researchers assigned a task and then cruelly engineered interruptions), but then found that they could significantly reduce the effect’s impact by asking the subjects, soon after the interruption, to make a plan for how they would later complete the incomplete task. To quote the paper: “Committing to a specific plan for a goal may therefore not only facilitate attainment of the goal but may also free cognitive resources for other pursuits.”

This ritual ensures that no task will be forgotten: Each will be reviewed daily and tackled when the time is appropriate. Your mind, in other words, is released from its duty to keep track of these obligations at every moment.

Your mind takes a lot of mental energy to constantly think about the incomplete task.

Write down the task, time, date, and location you’re going to resume the task. By writing down the task you need to work on. Your mind no longer needs to constantly think about the incomplete task. Your mind can finally get some rest.

Hard to Reach

In a 2012 article written for a New York Times blog, the essayist and cartoonist Tim Kreider provided a memorable self-description: “I am not busy. I am the laziest ambitious person I know.” Kreider’s distaste for frenetic work, however, was put to the test in the months leading up to the writing of his post. Here’s his description of the period: “I’ve insidiously started, because of professional obligations, to become busy … every morning my in-box was full of e-mails asking me to do things I did not want to do or presenting me with problems that I now had to solve.”

His solutions? He fled to what he calls an “undisclosed location”: a place with no TV and no Internet (going online requires a bike ride to the local library), and where he could remain nonresponsive. “I read. And I’m finally getting some real writing done for the first time in months.”

Tip#1: Make People Who Send You E-mail Do More Work

Most nonfiction authors are easy to reach. They include an e-mail address on their author websites along with an open invitation to send them any request or suggestion that comes to mind. Many even encourage this feedback as a necessary commitment to the elusive but much-touted importance of “community building” among their readers. But here’s the thing: I don’t buy it.

If you visit the contact page on my author website, there’s no general-purpose e-mail address. Instead, I list different individuals you can contact for specific purposes: my literary agent for rights requests, for example, or my speaking agent for speaking requests. If you want to reach me, I offer only a special-purpose e-mail address that comes with conditions and a lowered expectation that I’ll respond:

Tip#2: Do More Work When You Send Or Reply to E-mails

E-mail #1 “It was great to meet you last week. I’d love to follow up on some of those issues we discussed. Do you want to grab coffee?”

Process-Centric Response to E-mail #1: “I’d love to grab coffee. Let’s meet at the Starbucks on campus. Below I listed two days next week when I’m free. For each day, I listed three times. If any of those day and time combinations work for you, let me know. I’ll consider your reply confirmation for the meeting. If none of those date and time combinations work, give me a call at the number below and we’ll hash out a time that works. Looking forward to it.”

Tip#3: Don’t’ Respond

As a graduate student at MIT, I had the opportunity to interact with famous academics. In doing so, I noticed that many shared a fascinating and somewhat rare approach to e-mail: Their default behavior when receiving an e-mail message is to not respond.

Over time, I learned the philosophy driving this behavior: When it comes to e-mail, they believe it’s the sender’s responsibility to convince the receiver that a reply is worthwhile. If you didn’t make a convincing case and sufficiently minimize the effort required by the professor to respond, you didn’t get a response.

For example, the following e-mail would likely not generate a reply with many of the famous names at the Institute:

- Hi professor. I’d love to stop by sometime to talk about <topic X>. Are you available?

Responding to this message requires too much work (“Are you available?” is too vague to be answered quickly). Also, there’s no attempt to argue that this chat is worth the professor’s time. With these critiques in mind, here’s a version of the same message that would be more likely to generate a reply:

- Hi professor. I’m working on a project similar to <topic X> with my advisor, <professor Y>. Is it okay if I stop by in the last fifteen minutes of your office hours on Thursday to explain what we’re up to in more detail and see if it might complement your current project?

Unlike the first message, this one makes a clear case for why this meeting makes sense and minimizes the effort needed from the receiver to respond.

When you put yourself in a HARD TO REACH position, ask yourself.

What’s the ONE THING you can do this week such that by doing it everything else would be easier or unnecessary?

|

To-Do List

|

Success List

|

80/20 Pareto’s Principle

20% of the effort leads to 80% of the result.

EXTREME PARETO

I want you to go even smaller by identifying the 20% and then go even smaller by identifying the vital few.

No matter how many to-dos you start with, you can always narrow it to one.

You can take 20% of the 20% of the 20% and continue until you get to the single most important thing

25 X 20% = 5 X 20% = 1

Will Power

Roy Baumeister, has established the following important Truth about willpower: You have a finite amount of willpower that becomes depleted as you use it.

The most common desires these subjects fought include, not surprisingly, eating, sleeping, checking e-mail, social networking sites, surfing the web, listening to music, or watching television.”

Over time these distractions drained their finite pool of willpower until they could no longer resist.

The key to developing a deep work habit is to move beyond good intentions and add routines and rituals to your working life designed to minimize the amount of your limited willpower necessary to transition into and maintain a state of unbroken concentration. If you suddenly decide, for example, in the middle of a distracted afternoon to spend Web browning, to switch your attention to a cognitively demanding task, you’ll draw heavily from your finite willpower to wrest your attention away from the online shininess.

Such attempts will therefore frequently fail. On the other hand, if you deployed smart routines and rituals, perhaps a set time and quiet location used for your deep tasks each afternoon – you’d require much less willpower to start and keep going.

A frequently cited 2008 paper appearing in the journal Psychological Science describes a simple experiment. Subjects were split into two groups. One group was asked to take a walk on a wooded path in an arboretum near the Ann Arbor, Michigan, campus where the study was conducted.

The other group was sent on a walk through the bustling center of the city. Both groups were then given a concentration sapping task called backward digit-span. The core finding of the study is that the nature group performed up to 20 percent better on the task.

The nature advantage still held the next week when the researchers brought back the same subjects and switched the locations: It wasn’t the people who determined performance, but whether or not they got a chance to prepare by walking through the woods.

Directed attention: This resource is finite: If you exhaust it, you’ll struggle to concentrate.

We can think of this resource as the same thing as Baumeister’s limited willpower reserves.

The 2008 study argues that walking on busy city streets requires you to use directed attention, as you must navigate complicated tasks like figuring out when to cross a street to not get run over, or when to maneuver around the slow group of tourists blocking the sidewalk. After just fifty minutes of this focused navigation, the subject’s store of directed attention was low.

We have limited Willpower each day.

Your Willpower is like your cell phone battery. At night time when you charge your cell phone at the start of the day you have a full battery. Throughout the day when you use your cell phone. Your cell phone battery percentage goes down. At the end of the day your cell phone will have low battery. In order to keep using your cell phone. We need to charge it again.

Willpower works the same way. We want to use our Willpower wisely to install our number#1 Habit based on our dreams and goals that can help us achieve our dreams and goals.

Fixed schedule productivity

In the seven days preceding my first writing these words, I participated in sixty-five different e-mail conversations. Among these sixty-five conversations, I sent exactly five e-mails after five thirty-five conversations, I sent exactly five e-mails after five thirty p.m. I don’t send e-mails after five thirty. But given how intertwined e-mail has become with work in general, there’s a more surprising reality hinted by this behavior: I don’t work after five thirty p.m.

I call this commitment fixed-schedule productivity, as I fix the firm goal of not working past a certain time, then work backward to find productivity strategies that allow me to satisfy this declaration.

Nagpal early in her academic career she found herself trying to cram work into every free hour between seven a.m. and midnight ( because she has kids, this time, especially in the evening, was often severely fractured). It didn’t take long before she decided this strategy was unsustainable, so she set a limit of fifty hours a week and worked backward to determine what rules and habits were needed to satisfy this constraint. Nagpal, in other words, deployed fixed-schedule productivity.

She ended up earning tenure on schedule and then jumping to the full professor level after only three additional years. How did she pull this off? One of the main techniques for respecting her hour limit was to see drastic quotas on the major sources of shallow endeavors in her academic life. For example, she decided she would travel only five times per year for any purpose, as trips can generate a surprisingly large load of urgent shallow obligations (from making lodging arrangements to writing talks). Five trips a year may still sound like a lot, but for an academic it’s light.

To emphasize this point, note that Matt Welsh, a former colleague of Nagpal in the Harvard computer science department once wrote a blog post in which he claimed it was typical for junior faculty to travel twelve to twenty-four times a year. (imagine the shallow efforts Nagpal avoided in sidestepping an extra ten to fifteen trips!)

To create a fixed schedule productivity.

Awareness is the key to change: You can’t change what you don’t know. The biggest challenge is that we are sleepwalking through our choices. We are not even aware of the choices we are making.

For 3-5 days write down what you’re doing, time, and place on a piece of paper to identify how you spend your time to bring AWARENESS.

THE COMPOUND EFFECT by Darren Hardy – Keeping your Scorecard

Right this moment: Pick an area of your life where you most want to be successful. Do you want more money in the bank? A trimmer waistline? The strength to compete in an Iron Man event? A better relationship with your spouse or kids? Picture where you are in that area, right now. Now picture where you want to be: richer, thinner, happier, you name it. The first step toward change is awareness. If you want to get from where you are to where you want to be, you have to start by becoming aware of the choices that lead you away from your desired destination. Become very conscious of every choice you make today so you can begin to make smarter choices moving forward.

To help you become aware of your choices, I want you to track every action that is related to the area of your life you want to improve. If you’ve decided you want to get out of debt, you’re going to track every penny you pull from your pocket. If you’ve decided you want to lose weight, you’re going to track everything you put into your mouth. Simply carry around a small notebook . You’re going to write it all down.

Multi-Tasking + Task Switch

Sophie Leroy, a business professor at the University of Minnesota. In a 2009 paper, titled, “Why Is It So Hard to Do My Work?,” Leroy introduced an effect she called attention residue. In the introduction to this paper, she noted that other researchers have studied the effect of multitasking trying to accomplish multiple tasks simultaneously on performance, but that in the modern knowledge work office, once you got to a high enough level, it was more common to find people working on multiple projects sequentially: “Going from one meeting to the next, starting to work on one project and soon after having to transition to another is just part of life in organizations,” Leroy explains.

The problem this research identifies with this work strategy is that when you switch from some Task A to another Task B, your attention doesn’t immediately follow – a residue of your attention remains stuck thinking about the original task.

This residue gets especially thick if your work on Task A was unbounded and of low intensity before you switched, but even if you finish Task A before moving on your attention remains divided for a while.

Leroy studied the effect of this attention residue on performance by forcing task switches in the laboratory. In one such experiment, for example, she started her subjects working on a set of word puzzles. In one of the trials, she would interrupt them and tell them that they needed to move on to a new and challenging task, in this case, reading resumes and making hypothetical hiring decisions.

In other trials, she let the subjects finish the puzzles before giving them the next task. In between puzzling and hiring, she would deploy a quick lexical decision game to quantify the amount of residue left from the first task.

The results from this and her similar experiments were clear: “People experiencing attention residue after switching tasks are likely to demonstrate poor performance on the next task,” and the more intense the residue, the worse the performance.

Each time you get interrupted. It takes a minimum of 10min – 15min to concentrate your mind back to the task. You can’t afford to get interrupted or distracted. See how you can put yourself in a position so you won’t get interrupted or distracted.